Exploring the Deep:

The hidden human impact on deep sea ecosystems

While Earth may be a tiny rock when compared to the huge immensity of space, in every corner there exists a massive amount of life. The global population numbers well over 7 billion, while vast expanses of flora and fauna inhabit every city, forest, and water system.

Imagining a coastal ocean teaming with ecological diversity may not be difficult, but what about the unobserved blackness and enormity of the deep sea? So little is known about these ecosystems and the communities that thrive hundreds to thousands of meters below the sea’s surface, yet many scientists are devoting their time and research to explore these ecological wonderlands.

Imagining a coastal ocean teaming with ecological diversity may not be difficult, but what about the unobserved blackness and enormity of the deep sea? So little is known about these ecosystems and the communities that thrive hundreds to thousands of meters below the sea’s surface, yet many scientists are devoting their time and research to explore these ecological wonderlands.

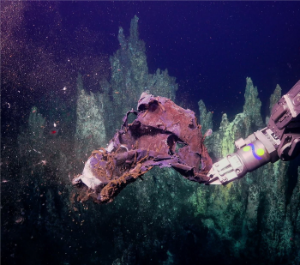

I had the privilege of being part of one such research expedition earlier this year under chief scientist Samantha Joye from the University of Georgia. The cruise, aboard the R/V Falkor, was a five-week voyage designed to explore the bottom depths of the Guaymas and Pescadero basins in the Gulf of California. The overall aim of the project, titled “Microbial Mysteries: Linking Microbial Communities and Environmental Drivers,” was to learn more about the microbes that thrive in the deep ocean. The Gulf of California is the perfect location for such an undertaking—the environment is a combination of hydrothermal activity and actively spreading seafloor. The young, rifting margins and explosive hydrothermal habitat offer a perfect setting for the microbes and other organisms living there.

The seafloor, not unlike a desert, covers huge expanses of flat bottom over kilometers of area and is often characterized by nothing more than sediment and the occasional octopus. The immensity of this dark void is a stark contrast to the cacophony of life found gathering in the veritable oases of these vent systems.

In all the hours spent in the dark room of the ROV van, eyes trained on the plethora of screens showing the seafloor, there was never a second when the validity of the research, time, or money spent to get there was questioned. The excitement of discovery lay at the forefront of our minds—to see the unseen, to study the brand new. But for every image of the beautiful and mysterious that flashed across the screen, images of something much more ominous awaited us. In the deep fissures present nearby, features resulting from the actively spreading seafloor, the refuse of humanity could be found. Trash—human waste like Mylar balloons, soccer balls, and fishing gear—lined the trenches. The most comical? A fully decorated, acrylic Christmas tree. The most tragic? A dead squid, choked on a discarded fishing net.

In all the hours spent in the dark room of the ROV van, eyes trained on the plethora of screens showing the seafloor, there was never a second when the validity of the research, time, or money spent to get there was questioned. The excitement of discovery lay at the forefront of our minds—to see the unseen, to study the brand new. But for every image of the beautiful and mysterious that flashed across the screen, images of something much more ominous awaited us. In the deep fissures present nearby, features resulting from the actively spreading seafloor, the refuse of humanity could be found. Trash—human waste like Mylar balloons, soccer balls, and fishing gear—lined the trenches. The most comical? A fully decorated, acrylic Christmas tree. The most tragic? A dead squid, choked on a discarded fishing net.

Astronauts do not go to space and expect to see floating polystyrene cups and exploding garbage bags. But for researchers of the deep sea—spaces no less alien than the solar system—that very expectation weighs heavily on our minds. I have seen the bottom depths of the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Gulf of California, and in every place there is trash. Anthropogenic waste has no place in the world’s oceans and waterways, yet the actions we take every day continually contribute to the ever-growing issue of pollution in these environments. While choices individuals make can have a small impact, for real and lasting change there must be an opinion shift on the global scale.

Many cities have begun banning single-use plastics and foam cups, and numerous startups have created innovative ways to recycle plastics already in existence. These efforts are just the beginning, but the pressure is on. Without broad and radical change, underwater desert oases like Big Pagoda will be nothing more than the unseen landfills of human detritus—the incredible ROV footage nothing more than the memory of an extinct world. We can be better. We must be better. The time is now.