International research, COVID-style

CCU’s Eliza Glaze combines technology and ingenuity to conduct collaborative research on pre-modern medical texts

As life during COVID continues its slow march, innovative scholars are finding creative methods for conducting research that would otherwise have required international travel. In keeping with other inventions sprung out of necessity, these new research techniques may in fact eclipse traditional methods even in a post-COVID world.

Eliza Glaze, professor in Coastal Carolina University’s Department of History, is one such resourceful scholar who, in forwarding her study of the intellectual and social histories of the Middle Ages, participated in virtual collaborative research on pre-modern medical history in Summer 2020.

Glaze worked on a grant project via Zoom and Google Docs with a group of colleagues at Oberlin College and Duke University to digitally transcribe Latin texts translated from Arabic by a physician named Constantine the African in 11th century Italy.

Glaze worked on a grant project via Zoom and Google Docs with a group of colleagues at Oberlin College and Duke University to digitally transcribe Latin texts translated from Arabic by a physician named Constantine the African in 11th century Italy.

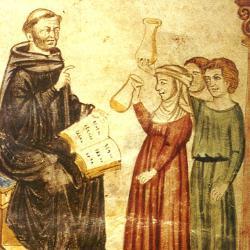

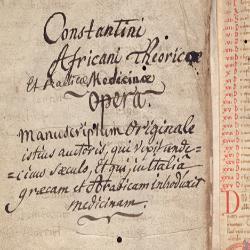

Constantine traveled from Tunis, in North Africa, to Salerno and then Monte Cassino, both in southern Italy. Over a period of 25 years, he translated more than two dozen medical treatises from Arabic into Latin. One of those texts was the Isagoge (Introduction to Galen’s Tegni), which became the first treatise in a standardized syllabus called the Articella (Little Art of Medicine), the introductory text used in European medical schools for nearly 500 years.

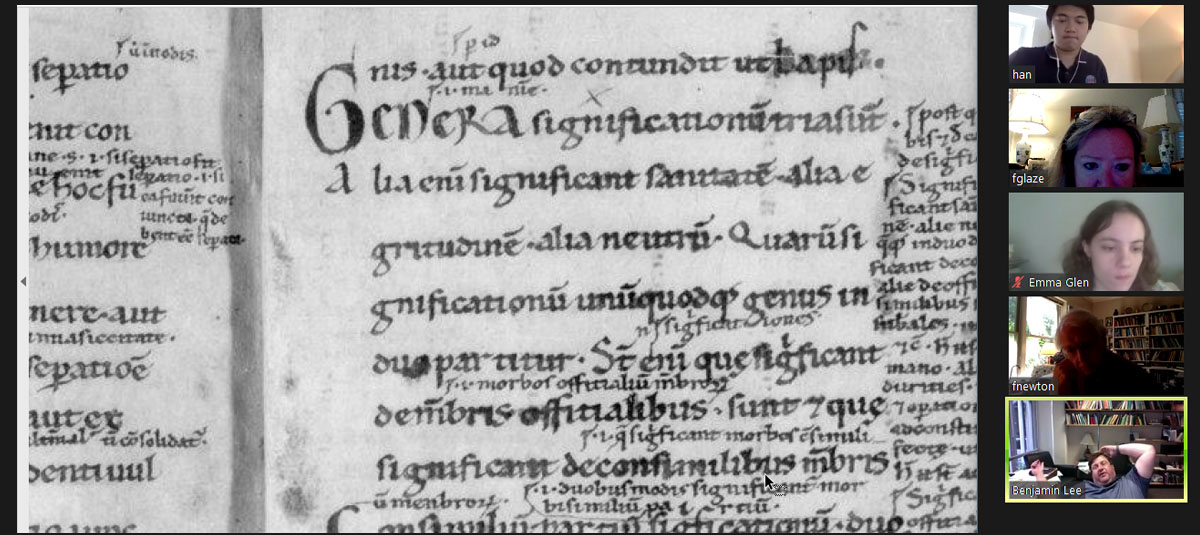

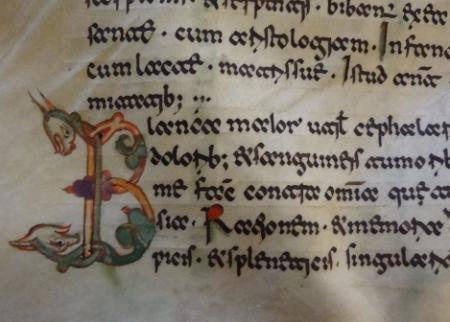

“We looked closely, word by word, at two very important manuscripts in draft versions – incomplete, imperfect versions – of what later became one of the most important medical educational texts in Europe from the late 11th through the 16th centuries,” Glaze said.

The inspiration for Glaze’s project, titled “Medicine at the Crossroads: Constantine the African, Salerno, and the early Articella,” was Francis Newton, emeritus professor of Latin at Duke University and Glaze’s former palaeography teacher and mentor, and Ben Lee, Classics professor and another Newton mentee at Oberlin College. After first reviewing one of the draft manuscripts back in the 1980s, Newton developepd a lifelong interest in untangling the earliest manuscripts of the Isagoge ; at age 93, he suggested a team effort among the three longtime colleagues and Latin experts. Lee secured the assistance of two Oberlin undergraduates in  Classics, Emma Glen and Han Yang, and the research team was complete.

Classics, Emma Glen and Han Yang, and the research team was complete.

Glaze and Newton had obtained digital photographs of the earliest manuscripts, which are permanently housed in libraries and archives across Europe. Together, over a two-month period, the group met 3 hours daily via Zoom to read, analyze, and transcribe the oldest of the manuscripts.

They have concluded that the original translation work was achieved through the teamwork of Constantine and his scribes, with the former dictating and the latter writing on wax tablets or scraps of parchment. Errors, inconsistencies and questionable meanings crop up frequently because of disparate dialects, erasures and corrections, and annotations made in the margins.

The modern team of scholars took turns reading aloud chapters from the text, written in Beneventan minuscule, the calligraphic script used in medieval southern Italy, which Glaze describes as “like Gothic, only scarier.” During the reading, one student transcribed the Latin text being read aloud, and the other annotated it in a Google doc. Then, Glaze said, they would discuss the material, including the translator’s and his scribes’ decisions, word by word, paragraph by paragraph, to develop an understanding of Constantine’s choices.

“We would say, ‘Ok, what is interesting and what is weird going on here? He’s got the grammar wrong here, he’s pronouncing this wrong, or else the translator working from the Arabic manuscript was reading out loud, and the scribe writing the draft down misunderstood,” Glaze said. “We considered questions like ‘How good was Constantine's Latin, or how clearly and correctly did he pronounce everything?’ or ‘How did Constantine determine technical terminology, like the names of diseases and theoretical concepts originally from Greek (by way of Arabic) not having Latin equivalents?’”

Because of the dual technologies of Zoom and Google docs, Glaze and company were able to hold long meetings with a live text, leading to more interaction and group critical thinking dynamics than would have been possible in traditional scholarly methods.

“In the past, we would have divided it up,” said Glaze. “We would have worked in splendid isolation, shared drafts via email, and then talked every weekend on the phone. But this made it really like being in a classroom or around a seminar table. I got a lot more done than if I had been working on my own at home.”

The project will continue in the form of a blog and a scholarly publication . In addition to the summer 2020 team,two CCU history majors, Raquel Brien and Bion Shoemaker, both veterans of Glaze’s Fall 2019 History of Medicine seminar, have been selected to assist in

Raquel Brien and Bion Shoemaker, both veterans of Glaze’s Fall 2019 History of Medicine seminar, have been selected to assist in

proofreading and cite-checking the blog and pre-publication draft as part of the process. “We want this project, which will have some translations of the text into English, to make sense to any educated reader, so Raquel and Bion will provide the final polish before the project goes live.”

For Glaze, the re-envisioned research process was not only a creative work-around within a restricted travel environment, but also a new model for pursuing collaborative scholarship.

“I learned so much more this summer than I normally do in a summer’s worth of research and research travel. Travel is exhausting, and no manuscript curators I know would allow a team of scholars to sit together over the actual manuscripts -- and talk for hours-- inside the libraries. But even better than progress made, we became a team with shared community,” said Glaze. “That is so valuable in stressful times. In some ways, for this project, COVID-induced travel restrictions turned out to be a real blessing in disguise.”