FEATURE | OCTOBER 26, 2020

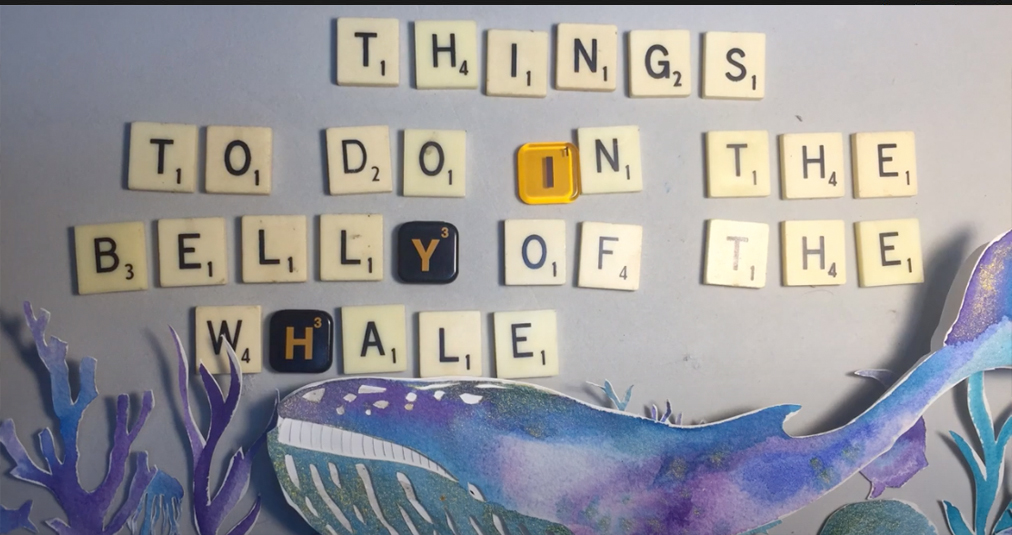

Things to Do

As the COVID pandemic has left millions of people with time on their hands, many have turned to poetry for solace – and found Dan Albergotti’s words.

While COVID-19 causes continuous pain and uncertainty across the globe, it also allows – no, requires – individuals worldwide to sit, think, and reflect. It provides time and space for people to consider their lives on a different scale. It offers a nurturing environment for those inclined to use their idle moments for connection and creation.

Within this context, numerous individuals spread across continents chose a poem as the focus of their endeavors. Individually, and without knowledge of the others, each selected Dan Albergotti’s “Things to Do in the Belly of the Whale” as a canvas upon which to pour their creative output. One artist in Iran, one in Australia, one in New York, one in Pennsylvania, and one in Massachusetts found the poem online and created a visual representation of it as a response to the COVID crisis. This global, organic contagion of poetic sentiment demonstrates how the power of art, combined with the power of the internet, can make connections, spread beauty, and offer healing among people even in the midst of a historic crisis.

Over the course of three months in spring 2020, Albergotti, CCU professor of creative writing in the Department of English, discovered each of these artistic pieces. None of the artists had contacted him before creation; the revelations were entirely serendipitous and virtual.

Over the course of three months in spring 2020, Albergotti, CCU professor of creative writing in the Department of English, discovered each of these artistic pieces. None of the artists had contacted him before creation; the revelations were entirely serendipitous and virtual.

“It seems like there was a little spirit going through the art world for the moment,” said Albergotti.

One artist created a stop-motion animated video with cut paper. One made animation from pencil drawings. One high school teacher asked his students to write their own version of the poem, yielding dozens of responses. One artist read the poem as a sock puppet.

As the various works appeared on his screen and accumulated in his download folder, Albergotti’s reaction grew from delight to wonder to astonishment.

“It feels surreal to see that your work has that kind of reach, that it can extend across the ocean and speak to somebody in some way,” Albergotti said.

The 20-year-old poem, with its central allusion to the biblical story of Jonah and the whale and its cataloguing of pastimes both frivolous and profound, offers fodder for a mind entrapped, both literally and figuratively. While the verse isn’t meant to apply to a specific event or scenario, its reference to physical and psychological restrictions has been clearly relevant to an eager audience during the COVID-19 crisis, when millions are confined to their homes with ample time for reflection.

“Things to Do” was in fact born in a time of waiting in his own life, Albergotti said, but the poem is less about himself than about his curiosity at his own emotions.

“Because of choices I’d made and circumstances I couldn’t control, I felt like I was treading water in my life,” said Albergotti. “I’d made a dramatic decision around that time to make a career change – at 35. I felt trapped and in stasis. But it’s not just how I felt about my life at that time. I was interested in the emotions I was feeling and their complexity. So, I hope the poem captures the complexity of coexisting contradictory emotions.”

“Things to Do” has generated widespread interest before, Albergotti said, especially from readers in difficult circumstances involving long lapses of unfilled time.

“Of all the poems I’ve ever written, it’s the one I’ve heard about from strangers most often, people emailing me out of the blue saying they found this poem and it spoke to them in some way,” Albergotti said. “I’ve heard from someone who was recovering from surgery, someone who was in prison, a lawyer who represented people in prison who wanted to share it with one of her clients, and someone who survived the Paradise, Calif., wildfire two years ago. It had seemingly spoken to people who felt like they were in a trap situation, a situation where their life was in stasis.”

One of the 2020 works based on his poem affected Albergotti especially deeply because of its beauty as well as the vast distance between the two artists: a stop-motion video created with cut paper by Pearl Taylor.

“I shared Pearl’s [on Facebook] right after I saw it the first time, because I was so moved by it,” said Albergotti. “I said ‘I just discovered it, and I’m in tears here to think that someone saw the poem and cared so much about it to make such a beautiful thing out of it.’ But also, I was just stunned. It’s one thing to have someone in New York do it, but she’s in Australia.”

Abby Sink, CCU graphic designer who is involved in the Edwards Live online initiative, tracked down Taylor and arranged an online interview between her and Albergotti, during which the two artists discussed their approaches to the poem and its relevance to the times. Taylor created her piece, an animated underwater world both beautiful and foreboding crafted from 700 photographs, as pastoral care outreach.

“The poem speaks to me,” said Taylor, who is also an art therapist. “It conveys beauty plus grief, the depths and heights of lived experience.”

Taylor had discovered the poem years before and reflected on it before the pandemic, during her nine-week recovery from a spine fracture.

“I became accustomed to being in the belly of the whale myself,” said Taylor during her conversation with Albergotti. “Then when COVID  started, I felt there was a lot of anxiety and distress in the world about, ‘What do we do when we’re at home?’ and I thought your poem had a settling effect – like, ‘We just need to wait.’ Since I had already been in the belly, I felt I could keep that quiet moment and help people just breathe.”

started, I felt there was a lot of anxiety and distress in the world about, ‘What do we do when we’re at home?’ and I thought your poem had a settling effect – like, ‘We just need to wait.’ Since I had already been in the belly, I felt I could keep that quiet moment and help people just breathe.”

Albergotti points to an individual line from the poem.

“’Be grateful you’re just here where you can rest and wait.’ The idea of being grateful in an unfortunate circumstance seems strange, but in a lot of ways, desperate circumstances can open our eyes to lots of things we’re blind to all the time.”

As for the global recognition of “Things to Do,” Albergotti said the knowledge that his work is comforting readers in a time of crisis is much more important than academic accolades.

“If the devil himself were to show up and say, ‘I’ve got a deal for you: You’re going to get the Nobel prize in literature, and you’re gonna get riches and all the acclaim that comes with it – you’re going to get interviewed and a super high-salary chair position somewhere. Here’s the one catch: all the acclaim will be entirely intellectual. People will call you brilliant, but nothing you write will ever have an effect on someone emotionally the way “Things to Do” has had on some people.”

If that were to happen, I’d kick that prize all the way back to Stockholm. That stuff is not worth this.”

In Fall 2020, Albergotti spent a six-month residency at the Amy Clampitt house near Lenox, Massachussetts. The nomination-only Amy Clampitt Residency program fosters the study, promotion, and production of poetry by housing and supporting selected poets-in-residence.

“Things to Do in the Belly of the Whale” stop motion video by Pearl Taylor on You Tube

Dan Albergotti and Pearl Taylor online conversation on Edwards Live

“Things to Do in the Belly of the Whale” pencil animation by Iranian artist Hayat Hasan on Instagram

“Things to Do in the Belly of the Whale” performed by sock puppet Claude the Reciter on YouTube