Flooding on the Waccamaw River over the past four years has impacted more local lives than any other natural event in recent times. Through scientific research and civic advocacy, Coastal Carolina University is committed to understanding and improving life along the Waccamaw.

Every other day for the past 20 years, Susan Libes has taken a water quality test sample of the Waccamaw River from the dock of her home near Conway.

It’s like I’m addicted,” said the longtime marine science professor and director of the Environmental Quality Lab (EQL) at Coastal Carolina University, “but I have to know what will happen next. Sometimes I drive my family crazy.”

Calm Before the Storm: Hurricane Florence approaching the South Carolina coast in September 2018.

Libes’ personal interest, perhaps obsession, with the river that runs by her home stems from her professional career in marine biogeochemistry. In 2004, she was instrumental in starting the Waccamaw Watershed Academy, which runs a volunteer water-monitoring program that involves more than 50 local citizens in regular water testing on the river from North Carolina all the way to Georgetown.

The health and well-being of the Waccamaw River, which touches the lives of everyone in Horry and Georgetown counties in some way, shape or form, is a matter of obvious public concern and a natural subject of research for CCU faculty. The frequent and disastrous flooding of the river since 2015, culminating with the record-shattering deluge following Hurricane Florence last year—which displaced a number of CCU students, faculty, staff and alumni—has magnified the river’s presence in our daily lives and elevated the importance of scientific river-related research by our faculty and research students.

Hot Water

It's the “wet” storms rather than the windy ones that have troubled our waters most significantly of late.

Paul Gayes and Len Pietrafesa know the climate is changing. The two scientists have spent the better part of their highly productive careers studying the complex interface of land, water and air along the Atlantic coast. The flood events of the recent past, along the North and South Carolina watershed that encompasses the Waccamaw, has convinced them of the need for more research, better technology and greater cooperation.

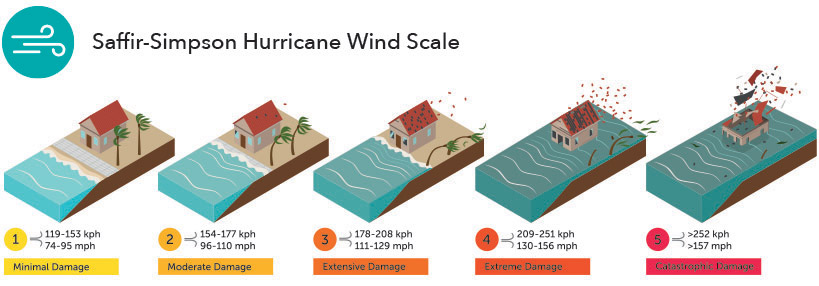

The familiar Saffir-Simpson scale that forecasters rely on to predict the strength of incoming tropical cyclone storms classifies hurricanes according to wind speed. But wind speed and storm surge are not necessarily the most salient features of a storm, as was proven this past fall with Hurricane Florence. It’s the “wet” storms rather than the windy ones that have troubled our waters most significantly of late.

Pietrafesa, research professor at CCU and former chair of the National Hurricane Center external advisory panel, first became aware of the wet storm phenomenon 20 years ago with Hurricane Floyd. The 1999 storm, which came ashore along Cape Fear in North Carolina, caused the worst flooding on the Waccamaw River in 70 years, along with significant loss of life and property.

What many people don’t remember, and what many of the official reports didn’t consider, according to Pietrafesa, is that Floyd was preceded by Hurricane Dennis less than two weeks prior. “Dennis sat off the coast of Cape Hatteras six and a half days whirling like a wheel, dropping copious amounts of rain and driving offshore waters into the coastal estuary, which compounded the problems caused by Floyd,” he said.

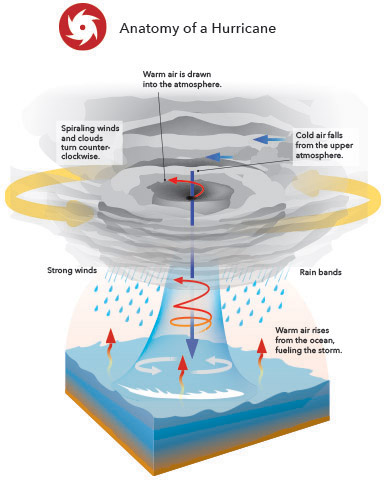

The more frequent appearances of wet storms are due largely to the rising temperature of ocean water, according to Pietrafesa. “The last four years have been the warmest ever recorded in the North Atlantic,” he said. “Water is heavy, it’s dense. Once the ocean absorbs all that heat, it retains it down to 2,000 feet. In fact, the ocean contains more heat in the topmost 10 feet of water than is stored in the entire atmosphere globally. When storms encounter warmer water, they slow down and get bigger. They love the heat. They’re being fed from below, and it’s like they’re at a buffet table and they’re feasting, getting fueled up with heat and moisture.”

Pietrafesa has observed a significant change in hurricane behavior in the past 20 years. “Typically, when a small storm spends at least six hours over the Gulf Stream, it gets bigger and intensifies, whereas in the past, a big storm tended to bust right across, not paying the Gulf Stream any attention. But now, the bigger storms are also slowing down over warm water, including the Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico.” As a consequence, these storms are becoming monstrously large and wet, like Joaquin (2015), Matthew (2016), Harvey (2017) and Florence (2018).

These slow-moving, rain-deluging events are changing the nature of inland flooding, in Pietrafesa’s view. “All this water creeps in, fed by offshore moisture, barely moving and creating a dam of water that corks up the mouths of the rivers. Our coastal plain is as flat as a bowling alley, so with massive lateral flooding there’s no place for the water to go.”

The combination of water, tides and wind bottling up the outlets prevents the system from purging itself as it would after a moderate local flood, creating a situation known as nonlocal forcing. “Fifty miles upstream, the water is rising but there’s no apparent local event causing it because it’s being corked at the mouth.” Sea level and wind patterns are also a part of the equation. When the water finally recedes, it’s at a snail’s pace. Pietrafesa says there hasn’t been a lot of research about this corking effect and its impact on coastal systems, and he is in the process of getting a grant to study it.

What's at Stake

Over the past 30 years, 210 of the nation’s weather events each caused more than $1 billion in damages.

Gayes believes the right way to study, understand and manage these climatological developments is a systems approach, collaborating across disciplines and with other universities to upgrade and refine the science, models, instrumentation and applications.

That’s our culture in this department, and we’ve been at it a long time,” said Gayes, director of the Burroughs & Chapin Center for Marine and Wetland Studies since 1989. “Working in silos to address environmental concerns—it has to die.”

These serious weather events are going to be more prevalent in the future, Gayes believes, and there is too much at stake not to take a broad-based approach. “In 2017, $316 billion was the cost of weather-related damages in this country, including floods and fires. That’s equivalent to 25 percent of the discretionary budget for the entire country, 10 percent of all federal expenditures. For example, over the past 30 years, 210 of the nation’s weather events each caused more than $1 billion in damages. Questions about the societal acceptance of global warming aside, whether it’s 100 percent human-driven or 5 percent, that’s a huge economic load.”

Shaowu Bao (standing), Len Pietrafesa and Paul Gayes operate the Hurricane Genesis & Outlook project, or HUGO, at CCU. After recent major floods caused by hurricanes, they are adjusting the prediction model to account for flooding in addition to wind and storm surge.

Satellite image of Hurricane Florence.

Water surge from Hurricane Florence on Market Street in Wilmington, N.C.

The impacts from these storms are far-reaching and complex. “There’s a lot of discussion about dredging, but unless we start to think about this as an integrated system, we’re just moving the problem around the box,” said Gayes. “If you dredge in one place, you may cause impacts in another community on the other side of the watershed. So it’s in everyone’s best interest to bring in a broader perspective and think about impacts 10 or 20 years down the road.”

Gayes foresees a day in the future when scientific observation capabilities have improved to the degree that it will be possible to predict the level and location of incoming floods with pin-point accuracy.

“Right now, the ability to forecast how a particular piece of property will be affected by an approaching flood is not very good,” said Gayes. “But with more and better and faster sensing equipment, we will be able to get observations that drive a better representation of the actual physics of how the water will behave. Remember that the flooding from Hurricane Florence was originally predicted to be worse in Georgetown than it actually turned out. The goal is to have the capacity of getting an accurate block-by-block model that will narrow our predictive capability to the size of a parking lot. Then when you merge all this data with the input of public health people and environmental quality people and energy policy people, you will be in a position to provide the information that a society needs to make wise decisions for the long term.”

Restoration Drama

The water rose into areas where it had never been before. Animals and organisms have to have oxygen to live, and the oxygen level went down to zero.

CCU professor Susan Libes takes water samples at least every other day from the Waccamaw River, a black water river. After Hurricane Florence, she said, the oxygen levels in the river were nearly depleted.

Crabtree Swamp is a long tributary branch of the Waccamaw’s Kingston Lake. It meanders around Conway’s eastern and northern boundaries, crossing heavily populated residential and/or business districts at Long Avenue, U.S. 701 North, U.S. 501 and El Bethel Road. This swamp drains 60 percent of the city. It’s been the site of some of the most damaging floods and the most frequent occurrences of E. coli and other chemical indicators of poor water quality.

Wildlife is washed ashore as oxygen levels plummeted in the Waccamaw River after Hurricane Florence.

Part of the problem dates back to the early 1960s, when an 8-mile stretch of the swamp was dredged to drain what was then a primarily agricultural landscape. The dredged canal changed the original course of the stream and disconnected it from the natural floodplain, eventually resulting in erosion, increased flooding, declining water quality and reduced wildlife habitat. The canal was poorly adapted to withstand climate change and related variations in local hydrology.

Back in the late 2000s, Susan Libes and a team of partners from the Horry County and Conway stormwater agencies led the first of a series of restoration projects designed to mitigate some of these problems. In 2009, this team, supported by CCU student researchers and volunteers, constructed a sloping “bench” of graded earth along a half-mile stretch of the stream to the east of U.S. 501, filling in part of the eroded channel and planting it over with more than 500 species of native trees and shrubs. The results of this effort were deemed successful, so the project was duplicated at other locations along the Crabtree Canal, and more are being planned for the future. In 2014, Horry County received the first Rain Catcher Award from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for the Crabtree project.

According to Libes, the major biogeochemical impacts of flooding were: very low and absent oxygen for several weeks; very high acidity (low pH); high total dissolved solids; high nutrients levels; and an algal bloom. “The low oxygen and pH led to fish kills and plant die off,” she said.

The persistence of elevated E. coli levels in Crabtree Canal prompted the City of Conway and Horry County to commission CCU’s Environmental Quality Lab to do a sophisticated microbial source tracking study. Samples are being collected along the canal from Oak Street to Long Avenue to capture run-off after rain events. “We are trying to pin down the host source to determine whether the bacteria is human or animal-sourced,” said Libes. The presence of human-sourced fecal bacteria would indicate a problem with sewage systems and/or septic tanks, she said.

“The reason we can identify the biogeochemical impacts of the flood is from comparison to long-term monitoring data that has been collected since 2006 by the 50 participants in the Waccamaw River volunteer water quality monitoring program and by the EQL’s staff since 2008,” said Libes. “We are collectively pooling all our different data types to get a big picture view over decadal time scales. One of the results of this monitoring was the development and implementation of the first watershed management plan in the state, which identifies research needs such as the microbial source tracking project in Crabtree Canal.”

Clare Nolan, who earned a master’s degree in CCU's coastal and marine systems science program in December 2018, worked on the Crabtree source tracking project as a grad student, and she now works full time in the EQL. The Watershed Academy and the EQL engage a large number of undergraduate and graduate students in research on the Waccamaw through internships, independent studies, honors theses and paid student worker positions.

The most unique environmental consequence of the Florence flood, in Libes’ view, was the unprecedented extent of vegetation decay caused by the height of the water (nearly 3 feet higher than the previous record set by Hurricane Matthew in 2016) and the slow rate of recession.

“The stench was nearly unbearable for a long period of time,” said Libes, who lives on the river. “The water rose into areas where it had never been before. Animals and organisms have to have oxygen to live, and the oxygen level went down to zero. Some animals can swim away and some can’t. If this were to happen once a week every year, even one week out of 52, it would take a considerable toll.”

Alumna Caroline Morton ‛15, a lab technician with CCU’s Environmental Quality Lab, and graduate student Andrew Crance with the coastal marine and wetlands studies program take water samples from Reaves Ferry on the Waccamaw River.

Oxbow Incidents

Reconstructing a history of floods on the Waccamaw River, especially those caused by hurricanes, going back hundreds and perhaps thousands of years.

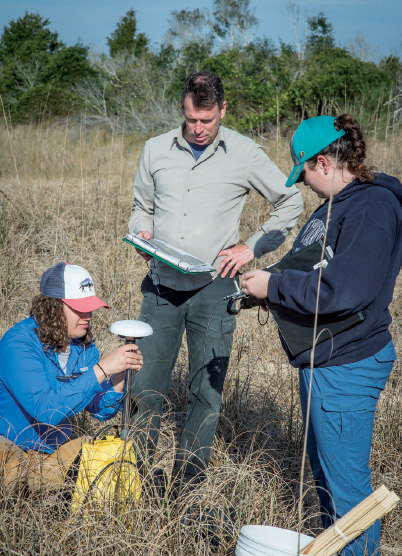

Professor Zhixiong Shen (right) with students Kaylea Cater and Morgan Sopov. Shen is studying sediment cores to better understand how flooding in the past may have been related to climate.

Zhixiong Shen, assistant professor of marine science, is a specialist in the study of river sediments. Last year, his research on the Mississippi River and the Mississippi River delta (the latter conducted while he was on the faculty at Tulane University) was featured in articles in Nature and Science Advances magazines. This coming year, he and his research associates and students will be spending a lot of time examining the river sediments of this region as part of two studies directly related to local flood events, past and present.

The first study, already underway, is investigating sedimentary traces of extreme floods that are preserved in the lakes in the floodplain of the Waccamaw River to determine their relationship to landfalling hurricanes of the past.

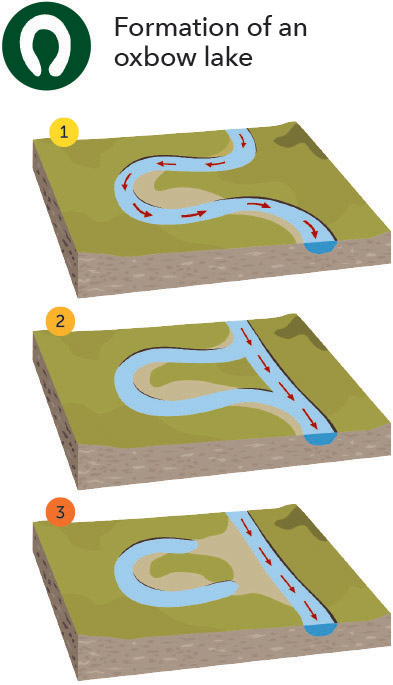

This aerial photograph of South Carolina coastal marshland shows the beginning of the formation of an oxbow lake, a U-shaped lake that forms when a highly bended portion of a river is cut off. (See graphic below.)

“The documented record of floods in this region only goes back about 70 years,” said Shen, “which is too short to understand whether or not these increasingly intense riverine floods are related to natural variability of the climate system or to anthropogenic [human-influenced] forces.”

Shen and his students are studying sediment core samples from oxbow lakes, U-shaped lakes that form when a highly bended portion of a river is cut off. Many of these formations occur along the Waccamaw in Horry County.

“We can determine from the size and composition of sediment if it was deposited by a flood event,” said Shen, who uses a laser particle size analyzer at CCU and a CT scanner provided through Conway Medical Center to analyze the sediments.

Shen hopes to reconstruct a history of extreme floods on the Waccamaw River, especially those caused by hurricanes, going back hundreds and perhaps thousands of years. The project, providing many research opportunities for CCU undergraduate and graduate students, will assist scientists not only in understanding the past but also what is likely to happen in the future.

Professor Till Hanebuth (center) and students Mimi Oliver and Madison Fink collect floodwater sediment in Georgetown, S.C.

In a related study that is funded by the National Science Foundation, Shen and Till Hanebuth, associate professor in the coastal and marine systems science department, together with scientists from Northeastern University, will collect and analyze floodwater sediment deposited directly by Hurricane Florence in the lower part of the Pee Dee River system. The purpose of the project is to “investigate the lateral and longitudinal patterns of sediment and associated contaminant deposition immediately following flooding caused by a landfalling hurricane. This research will clarify how extreme flood events carry sediments and contaminants from land to sea, a process affecting the health of people and ecosystems along the way.”

Personal Motivation

The Intracoastal Waterway bridge in Socastee after Hurricane Florence in September 2018. (right) Professor Jennifer Mokos, new to CCU, is already performing a research project that involves students interviewing residents about their decision-making process regarding evacuation when it comes to severe storms.

The Intracoastal Waterway bridge in Socastee after Hurricane Florence in September 2018. (right) Professor Jennifer Mokos, new to CCU, is already performing a research project that involves students interviewing residents about their decision-making process regarding evacuation when it comes to severe storms.

When Jennifer Mokos was in the second grade, her home in Lincoln Park, N.Y., near the Hudson River, flooded up to the kitchen countertops. The awesome power of the river was something she never forgot, and she developed an instinct for the prospect of rising water. Soon after she moved here to join CCU’s honors college faculty in August 2018, she explored her neighborhood for river tributaries. When Florence arrived a month later, her home was spared from flooding, but she started thinking about research projects.

Nearly everything Mokos has undertaken in her career has had an aquatic component. In her studies at Rutgers, SUNY and Vanderbilt universities, she carved an interdisciplinary niche combining geography, ecology, social health, art and community action. One of her recent studies focuses on the ecological restoration of rivers in southern California and its effect on homeless encampments there. She once worked for a New York City community nonprofit organization, involving children from low-income schools in a salamander monitoring project.

Associate professor Till Hanebuth and students Madison Fink and Mimi Oliver are collecting sediment in Georgetown, S.C., for analysis to better clarify how extreme floods carry sediments from land to sea.

(Above) The National Guard was deployed in downtown Conway after Hurricane Florence in September 2018. (bottom) Front Street in Georgetown in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence.

“My first research project at CCU, now in the planning stages, is a cultural study of the social and political aspects of large storm events and associated flooding,” she said. “The first stage will involve students interviewing local residents about their decision-making process as to whether to stay put or evacuate when a storm is coming. The purpose is to gain a better understanding of the diverse social and economic conditions that influence that decision. The results of the study could help inform emergency management practices while also hopefully dispelling stereotypes about why people do or don’t evacuate.” She expects to get the project underway in the fall of 2019.

Mokos is also involved in a civic engagement project spearheaded by Jaime McCauley of CCU’s sociology faculty, a Facebook initiative called Horry County Rising. The local civic advocacy forum invites nonpartisan community input on topics relating to flooding, growth, zoning, development and quality of life in an effort to help elected officials to make wise decisions for the long term about a range of issues relating to the social and environmental well-being of the county.

Higher Ground

In South Carolina, more than 1.5 million people live within 60 miles of the ocean.

Gov. Duane Parrish, director of the South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism; Tom Mullikin; chair, South Carolina Floodwater Commission and CCU professor; Henry McMaster, governor of South Carolina; Pamela Evette, lieutenant governor; and Joe Riley, former mayor of Charleston, plant marsh grass at a floodwater commission meeting in Fall 2018.

Making wise decisions for the long term through broad stakeholder input is a perfect description of Tom Mullikin’s overall goal as chairman of the South Carolina Floodwater Commission. Mullikin, a CCU research professor since 2011, is no stranger to setting high goals—and reaching them. In fact, he has built into his life plan a set of goals that are the stuff of swashbuckling adventure movies. When he meets them, he will be the first person to dive all the world’s oceans and climb the highest mountains on all seven continents.

He is well on his way, but right now he’s focused on the work of the commission, which Gov. Henry McMaster created and chose Mullikin to chair this past October, while the floodwaters were still receding along the Waccamaw.

Sitting in his office in the Coastal Science Center, just down the hall from Gayes, Pietrafesa and Libes, Mullikin says he sees tremendous opportunities as well as challenges in the work ahead.

“There are three main issues that make us different in South Carolina,” said Mullikin, an internationally respected environmental lawyer. “One is extreme flash flooding during local rain events, such as we see frequently in Charleston. Two is coastal storm surge off the ocean. Three is transboundary flooding, which we see when the rivers of South Carolina flood their banks because of watershed saturation in North Carolina due to extreme weather from the Gulf. Each one requires a different strategy.”

Mullikin and McMaster are proponents of a “big tent” approach when it comes to the composition and functions of the commission. “South Carolina has the best resources in the world,” said Mullikin. “We’re harnessing the experience, ingenuity and the intellectual capital of our research institutions, technical colleges, military personnel and civil expertise, touching every agency in the state.”

Members include more than 50 business, governmental, political and academic leaders from across the state, including several of Mullikin’s faculty colleagues in CCU's College of Science. “My graduate students here in coastal and marine studies are also involved. They’re brilliant—and eager to apply what they’re learning.”

On the wall of Mullikin’s office is a chart outlining the 10 volunteer task forces he has created that will focus on specific projects: artificial reef, living shoreline, infrastructure and shoreline armoring, smart river and dam security, grid security, landscape and beautification protection, national security, stakeholder engagement, federal funding, and economic development.

Gov. Henry McMaster (right) appointed Tom Mullikin (left) to chair the South Carolina Floodwater Commission. (middle image) Paul Gayes, director of the Burroughs & Chapin Center for Marine and Wetlands Studies at CCU, is also a member of the S.C. Floodwater Commission. (below) Tom Mullikin.

Mullikin says the commission will explore and study best practice solutions to flooding problems in other parts of the country and world, from Sacramento, Calif., to the Netherlands to the Fiji islands. The task forces will concentrate on solving problems. “We’re not going to debate the why and where of climate change. It’s not a hypothetical. In South Carolina, more than 1.5 million people live within 60 miles of the ocean. We’re going to focus on taking care of our state, taking no notice of special interests.”

In addition to projects designed to mitigate the environmental damage caused by storms, such as an artificial reef system, drainage and dams, and vegetation restoration, Mullikin believes that one of the outcomes of the commission’s work will be more extensive opportunities to use the state’s waterways for leisure and recreation. “We live in one of the most beautiful places on earth right here,” he said.

At the commission’s highly publicized first full meeting in Columbia on Dec. 20, Mullikin told the group, “We intend to make water our friend. We will lead everyone to higher ground.”